Nothing arrives. Everything leaves a trace

These images are not records, but residues.

They mark thresholds, not destinations.

What is seen is incomplete by design.

What is felt cannot be recalled.

Core Currents (Working Constellation)

Absence as a form of presence

Sites that feel inhabited without activity; traces left behind like warmth in an empty room.Recognition without recollection

A knowing that arrives without origin; memory stirred without story, name, or proof.Thresholds and hesitation

Doors, windows, paths, fences; liminal structures where movement is implied but never completed.Reflection as instability

Images returned imperfectly; surfaces that bend, fracture, or interrupt vision rather than clarify it.Portals and non-arrival

Depth suggested but withheld; passages that pull the gaze inward without permitting entry.The overlooked and the mundane

Ordinary British spaces resistant to spectacle, charged quietly through repetition and neglect.Walking as rite

Slow movement, drifting attention, lingering; a way of seeing that emerges through patience rather than pursuit.Withholding as discipline

Minimal acts of image-making; refusal of declaration, explanation, or closure.Trace and residue

Wear, marks, stains, and surfaces bearing witness to what has passed without recording it.Atmosphere over event

Stillness, pause, and tone privileged over action or revelation.

Entry Point

Secondary Lines of Inquiry (emergent, not separate)

Research may circle around:

memory as a spatial phenomenon rather than a narrative one

photography’s capacity to conjure meaning through absence

restraint as an ethical position within observational practice

vernacular British environments as sites of shared yet anonymous haunting

Binding Statement (optional)

The work attends to ordinary environments as reflective and transitional sites, where memory surfaces obliquely, recognition occurs without explanation, and meaning remains deliberately unresolved.

Initial Touchstones

Todd Hido

Stephen Shore

William Eggleston (tentative)

Texts of Invocation

Absence, Afterimage, the Everyday

Camera Lucida – Roland Barthes

On what lingers after the moment has passed; the photograph as emotional residue.The Photograph as Contemporary Art – Charlotte Cotton

Locating contemporary practices that resist spectacle and overt narrative.Photography and Place – Jeff Malpas (ed.)

Grounding the image in spatial experience rather than story.

Walking, Drift, Non-Destination

The Practice of Everyday Life – Michel de Certeau

Walking as quiet resistance; movement as a form of inscription.London Orbital – Iain Sinclair

Space generating meaning through repetition and refusal of closure.A Field Guide to Getting Lost – Rebecca Solnit

Not-knowing as value; delay, wandering, and the productive fog of disorientation.

Reflection, Threshold, Passage

The Poetics of Space – Gaston Bachelard

Corners, houses, interiors, and the psychic charge of thresholds.The Arcades Project – Walter Benjamin

Glass, passageways, reflections; fragments of modernity as haunted architecture.Transparency – Colin Rowe & Robert Slutzky

The difference between what is seen and what is sensed.

Portals

Visual Kinships (not lineage, but proximity)

Paul Graham – Britain, waiting, in-between states

Jem Southam – Time, return, slow transformation

Raymond Moore – Absence, surface tension, quiet unease

Stephen Shore – Neutrality, surface, the unremarkable

Tacita Dean – Disappearance, orbiting subjects, loss without spectacle

Memory, Trace, Non-Narrative Meaning

Memory and Architecture – Eleni Bastea (ed.)

Memory as spatial accumulation rather than personal recollection.The Poetics of Ruins – Dylan Trigg

Atmosphere, lingering presence, and the pull of what remains.Ghosts of My Life – Mark Fisher

Hauntology, British spaces, futures that never arrived.

Use of Sources (practical ritual)

No need for total immersion.

Select one or two primary texts (e.g. Bachelard, Solnit)

Sit with two or three photographers

Extract phrases, tensions, atmospheres

Reflect as much on divergence as alignment

Supplement with moving-image material:

Louis Stettner – In Memory’s Light

Robert Frank – Leaving Home, Coming Home

Sally Mann – What Remains

Anders Petersen – Without Longing No Image

Harry Gruyaert – Harry Gruyaert, Photographer

Mirrors and Windows

Mirrors and windows are central to my work, not only as objects but as guiding ideas. They reflect the shifting nature of perception I want to explore, showing how looking can challenge fixed meanings and invite uncertainty.

I see mirrors more as sources of reflection than as physical objects. For me, reflection is indirect and depends on light, angle, distance, and situation. It doesn’t give a clear or personal view of the self, but instead offers fragments of recognition shared between the environment and the viewer. Reflections often show up by chance and only for a moment, disrupting vision instead of clarifying it. In this way, reflection feels similar to memory: partial, unreliable, and easily distorted.

In the same way, I think of windows not just as viewpoints but as portals. A window lets us see into another space, but it also sets a boundary we can’t cross. It suggests movement or change, but never lets us arrive. Instead of giving access, the window keeps the viewer at the edge, aware of what’s inside but unable to enter. This feeling of hesitation matters to my work, as I’m interested in moments where something seems present but just out of reach.

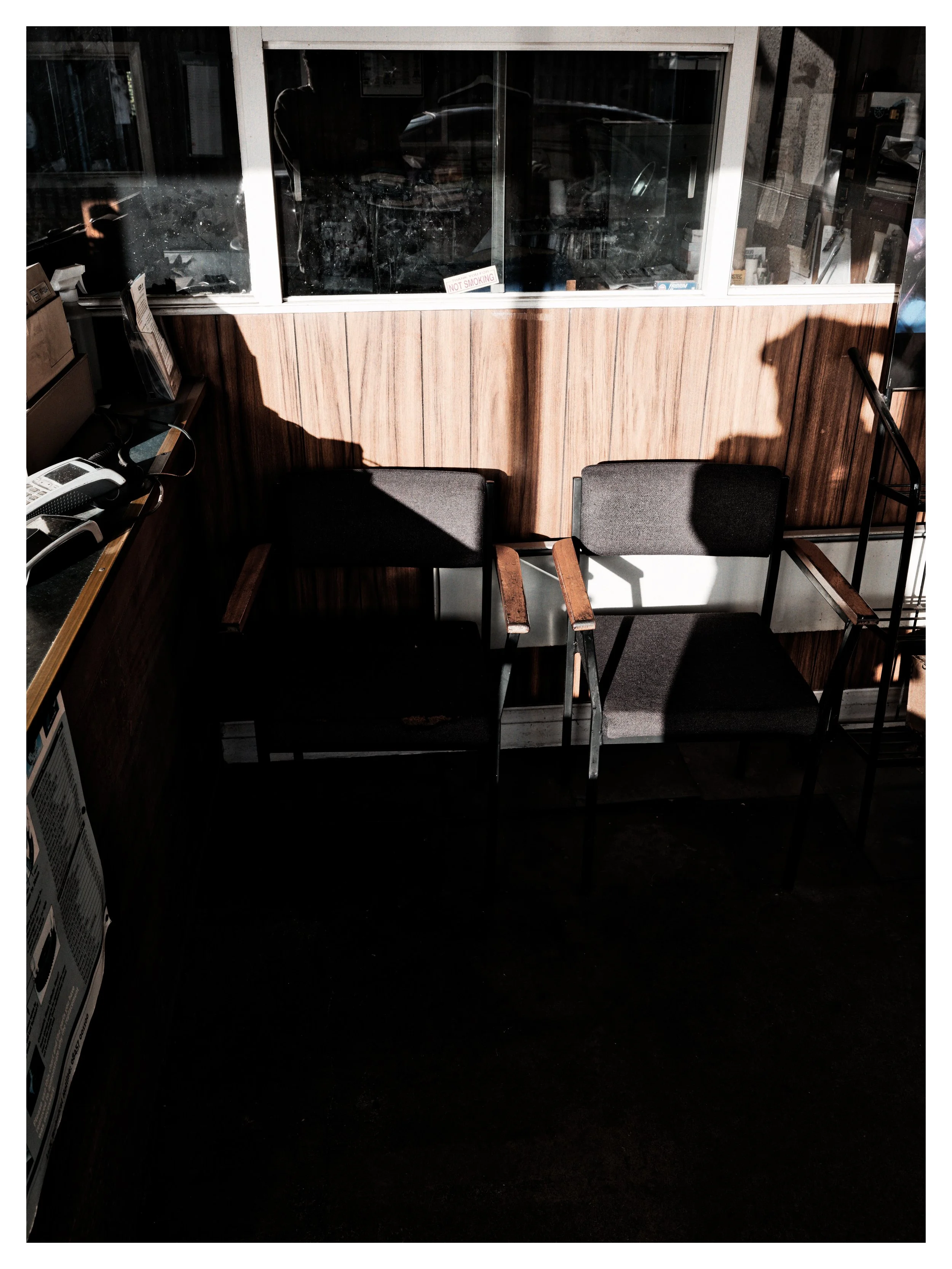

The image I shared for this theme shows a reception area seen through a large glass pane. At first, it looks simple and practical, but the glass makes the scene more complex. Reflections from outside cover the inside space, making it look flat and visually confusing. The word “Reception” is mirrored and repeated, turning from an invitation into a barrier. What should feel welcoming instead creates distance. The room looks empty but is clearly set up for use, hinting at presence through absence.

This image connects to my wider interest in recognising places that feel familiar but don’t offer a clear story or explanation. The glass acts as both a mirror and a window, showing the outside while partly revealing the inside, but never fully doing either. This double role shows how mirrors and windows can distort just as much as they reveal, all depending on where you stand and how you look.

These ideas resonate with Gaston Bachelard’s writing on interior and exterior space, particularly his examination of thresholds and domestic architecture as psychologically charged sites, rather than neutral structures (Bachelard, 1994). Similarly, Walter Benjamin’s writing on glass and modernity considers transparency not as clarity, but as something that produces estrangement and fragmentation (Benjamin, 1999). In photographic terms, this aligns with practices that resist spectacle and narrative certainty, allowing images to remain unresolved.

Photographers like Paul Graham and Raymond Moore have shaped how I see ordinary places as carrying emotional or psychological meaning without obvious drama. Their work shows how holding back, focusing on surfaces, and creating atmosphere can give meaning through what isn’t shown. More generally, this fits with modern photography that treats the image as a place for hesitation, not just explanation (Cotton, 2020).

The Stone Tape (Kneale, 1972) is a helpful comparison for my work, as it treats memory as something held in places, not just by people. The film suggests that spaces can absorb and replay emotional or traumatic events, making buildings feel like they hold traces of the past. This matches my interest in absence as a kind of presence and in places that seem occupied even when empty. In my work, meaning comes through atmosphere, surfaces, and traces, not through clear stories or images. Like The Stone Tape, my images avoid easy explanations and keep things uncertain, focusing on everyday British places as sites of hidden memory where recognition happens without full understanding.

My visual style is similar to British films that create psychological tension by holding back, using familiar settings, and leaving things unsaid. Films like Possum (Holness, 2018), Dead Man’s Shoes (Meadows, 2004), and A Gun for George (Holness, 2011) focus on mood and suggestion instead of clear stories.

Thinking back on this first week, I see that mirrors and windows are more than just visual themes in my work. They are ways I explore memory, access, and absence. Both depend on where you stand and how you look; both can reveal, hide, change, or block what you see. This instability is key to how I want my images to work—not as answers, but as spaces for reflection and transition, where recognition can appear without full resolution.

Bachelard, G. (1994) The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press.

Benjamin, W. (1999) The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cotton, C. (2020) The Photograph as Contemporary Art. 3rd edn. London: Thames & Hudson.

Graham, P. (1986) Beyond Caring. London: Grey Editions.

Moore, R. (1977) Every So Often. London: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Possum

Holness, M. (2018) Possum. [Film]. UK: BFI / The Rook Films.

Dead Man’s Shoes

Meadows, S. (2004) Dead Man’s Shoes. [Film]. UK: Warp Films.

A Gun for George

Holness, M. (2011) A Gun for George. [Short film]. UK: Warp Films.

The Stone Tape

Kneale, N. (1972) The Stone Tape. [Television film]. UK: BBC.

Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

Fisher, M. (2014) Ghosts of my life: Writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures. Winchester: Zero Books.

Fisher, M. (2014) ‘What is hauntology?’ in Ghosts of my life: Writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures. Winchester: Zero Books.

Methods and Meaning

In The Shadow, the image of a lone figure standing between trees reflects Calle’s method of relinquishing authorship and adopting the visual language of surveillance. By employing a private investigator to follow and photograph her, the resulting image appears almost incidental: the figure is partially obscured, viewed from a distance, and caught in a moment of stillness rather than action. This absence of deliberate composition reinforces the sense that the photograph functions as evidence rather than expression. The investigator’s neutral, factual notes further strip the figure of interiority, reducing the subject to a behavioural trace. Through this process, Calle’s method directly shapes the presentation of the finished work, where space becomes a site of observation rather than lived experience, and the moment is fixed as documentation rather than narrative.

This image by Henri Cartier-Bresson sits in sharp contrast to Sophie Calle’s The Shadow. Despite some surface similarities, both images rely on distance, partial obstruction, and observing an unaware subject. However, Calle’s image feels extracted and evidential. Cartier-Bresson’s is resolved and intentional. The child moving through the stepped architecture is caught at a precise, balanced moment. Light, shadow, and form align instinctively. Composition here is central, not incidental.

Methodologically, the difference is stark. Cartier-Bresson works through immersion and anticipation. He waits for what he famously termed the decisive moment. Calle, by contrast, removes herself from authorship and delegates vision to a private investigator. She foregrounds process over intuition. Where Cartier-Bresson humanises through form, Calle depersonalises through structure. One seeks harmony; the other cultivates unease.

Calle, S. (1981) The Shadow. Black and white photograph. In: Suite Vénitienne / The Shadow. Paris: Éditions Xavier Barral.

Cartier-Bresson, H. (1961) Greece. Black and white photograph. In: The Decisive Moment. New York: Simon and Schuster.

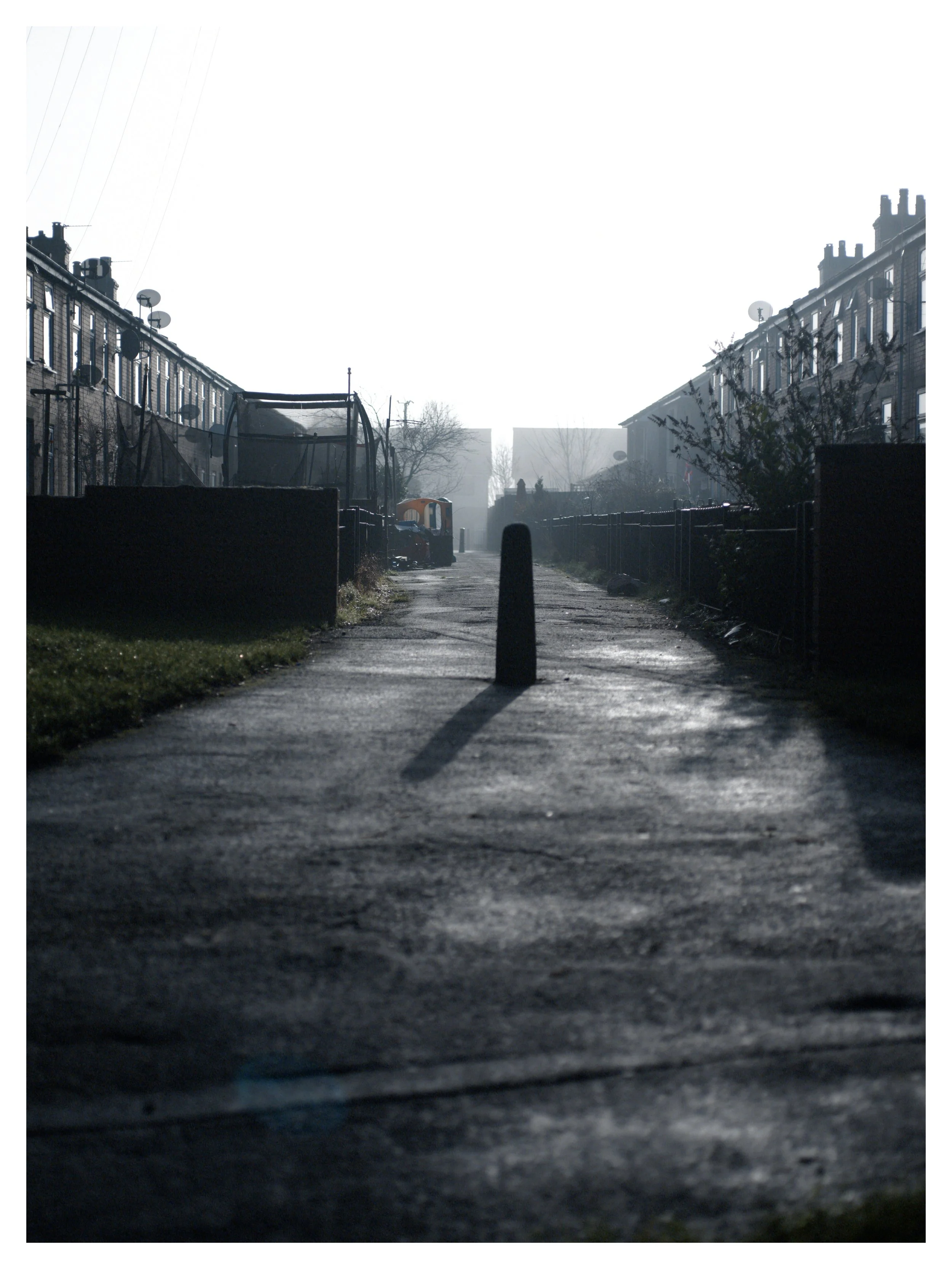

Barriers, Residue, Lost Futures

These images came together gradually, with no rush or set goal. They grew out of walking, lingering, and letting spaces stay unresolved. What you see are not events, but traces left behind—signs of use, habitation, and intention that remain after meaning has faded. Fences, windows, barrels, cars, water, and walls each act as thresholds instead of main subjects, keeping the viewer in a state of suspension.

Here, photography is less about capturing and more about tuning in. The camera senses what remains, instead of showing what stands out. Vision is often blocked by wire, glass, branches, or grime—not as a mistake, but on purpose. These barriers slow down the viewer and remind us that access is never simple. The images do not open doors; they show where doors once mattered.

This work quietly connects to Sophie Calle’s use of distance, watching, and holding back, where absence becomes a kind of presence (Calle, 2003). But unlike Calle’s stories, these images avoid chasing answers or revealing secrets. The viewer’s gaze is involved but left unresolved, staying at the edge of understanding without clear explanation.

These images also intentionally avoid the decisive moment linked to Henri Cartier-Bresson (Cartier-Bresson, 1952). Instead of seeking perfect timing, they embrace delay, misalignment, and hesitation. Blur, blockage, and underexposure—usually seen as mistakes—are used on purpose to resist spectacle and certainty. Nothing happens, but time still moves forward.

This atmosphere is shaped by Mark Fisher’s writing on hauntology and lost futures, in which spaces are charged by futures that failed to arrive (Fisher, 2014). The environments pictured here are not ruins, but they are no longer fully operational. They exist between memory and forgetting, producing unease without nostalgia. The future does not announce its absence; it simply stops appearing.

This work acts like a quiet kind of magic. It does not summon, but listens. It does not reveal, but leaves traces. A broken lens set at f/2.8 becomes a ritual limit, with the aperture left open to uncertainty. Meaning is held back, letting the viewer finish the story. What is left are barriers that do not fully block, windows that do not fully open, and reflections that never settle. The ritual never ends. Something always lingers.

Calle, S. (2003) Double Game. London: Violette Editions.

Cartier-Bresson, H. (1952) The Decisive Moment. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Fisher, M. (2014) Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester: Zero Books.

Barriers, Residue, Lost Futures

This work is guided by careful observation instead of a set plan. It pauses at boundaries, noticing small changes, traces, and disruptions that feel familiar but are hard to remember clearly. Instead of searching for meaning directly, it lets meaning build up slowly through obstacles, delays, and refusals. The images act as witnesses, not as proof, holding knowledge that cannot always be put into words. Time feels broken, the future is uncertain, and familiar places seem out of order. What is being followed stays unnamed, sensed only through what repeats or is missing. The search goes on, but only as a faint trace—just enough to show a direction, never enough to reach a final answer.

Big Ideas, Real Impact.

Every event we host is designed with intention, from the atmosphere we create to the way each session flows.